Spine Challenger North— a 160 mile, non-stop race along the Pennine Way in winter, battling everything the British weather can throw at us in sub-zero temperatures. It’s a gruelling challenge. 2024 was a tough year and didn’t leave much time for writing blogs so I’m behind on a few, however, I was determined to get this one out before 2025 takes over.

Spine race media were kind enough to interview me before the race acknowledging I’m known as The Running Granny and I thought it might be helpful to give a little background to this alias.

The Running Granny is more than a nickname—it’s a mission to challenge age-related stereotypes and prove that adventure, resilience, and growth have no expiration date. At a time when many embrace retirement, I chose to redefine what it means to be a “granny” through running, transforming it into a narrative of strength and possibility.

With every mile, I challenge the belief that ageing limits potential. My journey, shaped by decades as an orthopaedic surgeon and advocate for older adults, has revealed the devastating impact of poor health in later life. Witnessing systemic failures in healthcare, I asked: “How can we prevent this?”

The answer lies in personal empowerment. The Running Granny is not just about my achievements—it’s about inspiring others to build a ‘health pension’ through small, consistent wellness investments, ensuring a healthier, more active future.

My message is simple – we can all take steps to:

-

Prevent the onset of chronic conditions

-

Limit the progression of existing health challenges

-

Maintain physical and mental resilience as we age

-

Challenge the narrative of inevitable decline

By embodying this philosophy through running and active living, I aim to inspire others to see ageing not as a process of deterioration, but as an opportunity for continued growth, challenge, and vitality. I set up a social enterprise, Going for Old community Interest company, and deliver Healthy Ageing and Bone Health workshops as well as spreading the word with various speaking engagements.

Discovering Potential: My Ultra Running Journey

At 53, I found ultrarunning—not through talent, but through discipline and a desire to explore my limits. This journey became more than a sport; it symbolized personal growth and human potential.

Progress isn’t about giant leaps but small, deliberate steps—what I call the ‘art of the possible.’ We often impose limits on ourselves, yet reality proves them false. Whether mastering a skill or completing an ultrarun, pushing beyond self-imposed barriers is transformative.

The myth that ageing means decline is both incorrect and harmful. Our bodies adapt to the demands we place on them—‘use it or lose it’ applies to both physical and mental potential.

Ultrarunning, for me, isn’t about miles—it’s a statement that age is not a limitation but an opportunity for continuous challenge and discovery. No matter when we start, possibilities remain, and we’ll find a community to share the journey.

The Spine Race: From Dot Watcher to Participant

For years, the Spine Race captivated me—I was a mesmerized dot watcher, awed by images of ice-encrusted runners at Gregg’s Hut. The sheer extremity felt beyond my reach, especially given my susceptibility to hypothermia.

Volunteering for eight days at checkpoints from Hawes to Kirk Yetholm changed everything. I witnessed both the front-runners and the determined stragglers, gaining a profound respect for the race’s relentless physical, mental, and emotional demands. Inspired but aware of my limitations, I nurtured a quiet belief: where there’s a will, there’s a way.

After years of injury and recovery from long COVID, I entered the 2024 Spine Challenger North, knowing a finish was unlikely. I DNF’d at Dufton after 54 miles, but every step fueled my resolve. Just two weeks later, I committed to the 2025 Winter. However, as with any journey of significance, the path was never going to be straightforward.

Journey to the Spine Race: Preparation Against the Odds

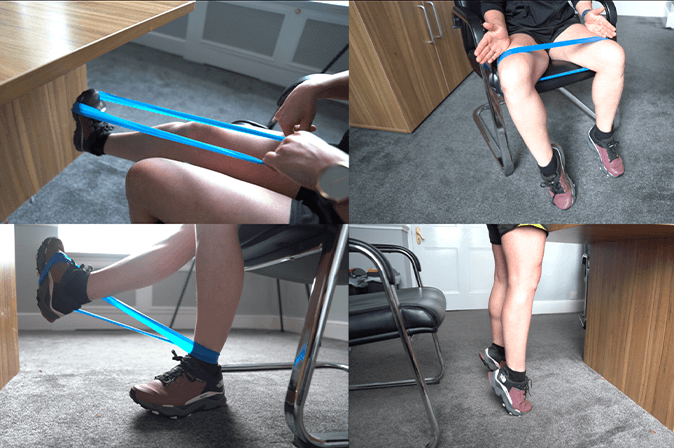

My journey to the Spine Race was anything but straightforward. Knee issues led to surgery, and my recovery followed a strategic, holistic approach. Three weeks of intensive prehabilitation focused on knee stability, limiting other activity. After mid-August surgery, my coach meticulously aligned my training with my surgeon’s plan.

Four weeks post-surgery, I eased into movement—30 seconds of treadmill running followed by two-minute walks. By eight weeks, I was on gentle trails. Though the surgery was successful, recovery was complex. Persistent swelling remained a challenge, only partially alleviated by steroid injections in December. These finally allowed me to carry a pack on hills from December 13th—just a month before the race. I was advised that swelling would likely be a long-term issue despite surgery.

Adjusting to my 7.5-8kg pack was tough, but accepting its limitations early helped manage frustrations. My preparation was far from ideal, but I took a pragmatic approach. This wasn’t about running—it was about endurance. Skills, strategy, and mental resilience mattered more than physical perfection.

Beyond the challenge, this race held deeper significance. After a difficult 2024, it was my way of reclaiming control—starting 2025 on my own terms. Preparation has always been my strength. I spent a full week organizing drop bags and checkpoint strategies to make race administration almost automatic, crucial given the inevitable sleep deprivation.

The Spine Challenger North is structured around three major checkpoints, dividing the race into four stages. As a continuous event, participants have flexibility in sleep strategy. While checkpoints offer the best rest options, conditions and individual needs dictate when to stop.

A Challenging Journey: Navigating The Spine Race Terrain

Recent heavy snow had transformed the landscape, but the previous day’s warmth triggered a thaw, creating treacherous conditions. Thick ice gave way to slush, making ice spikes essential for safe passage. Ascending Great Shunner Fell, runners struggled on the slippery terrain, hastily attaching spikes. Usual trails were buried, forcing us to forge new paths. While 2024 had been dominated by ice, this year’s slower route felt more navigable to me.

Farmland sections were equally brutal—tracks became knee-deep freezing trenches, turning each step into a mental battle. The thought of 150 more miles ahead only added to the strain. Reaching the Tan Hill Inn took far longer than expected, its shelter a brief sanctuary after a relentless morning. But this was just the beginning—days of continuous movement, endless hills, and winter’s unpredictable wrath lay ahead.

After a warm meal and gear adjustments, I stepped back into the white wilderness. The wind howled as I braced for the crossing of Sleightholme Moor—unaware of the unexpected challenge that awaited.

When Snow Hides the Abyss: A Near Miss on the Winter Moor

About a mile on, I encountered a wide, snow-covered bog. Tracks in the snow suggested a safe route, but such signs can be deceptive. As I cautiously stepped forward, the ground gave way. My left leg plunged downward, my right foot found only empty space, and ice-cold water swallowed me up.

Time slowed as I grabbed for my disappearing walking pole. Probing for solid ground revealed nothing but void beneath the deceptive snow crust. The bog gripped me tighter with every movement. Freezing water crept past my knees, my left arm submerged to the armpit, the sub-zero air turning my wet clothes into a serious threat. Alone on the moor, the danger was stark.

With sheer effort, I flipped onto my back and used my poles to drag myself out, heart pounding, cold seeping into my bones. Another runner soon arrived, and my warning likely spared them from the same fate. Together, we found a safer crossing, but the moor continued its ruthless reminders—hidden hazards at every turn.

Those deceptive tracks had nearly led to disaster. In winter, snow-covered bogs are a gamble, and survival often depends on experience, instinct, and a bit of luck.

Pressing On

My new companion, Petra, and I navigated carefully through unseen river crossings in the dark. The nine miles from Middleton to Langdon Beck checkpoint passed uneventfully, though we noted the river Tees had encroached onto the path, likely forcing a diversion at Cauldron Snout. At the A66, Kim, leading the Spine Race, passed us. I was glad to see him again at the checkpoint, though concerned to hear his legs were faltering. Thankfully, he recovered and went on to claim a well-earned victory.

After eating and sorting my gear, I hoped for sleep, but with no available beds, I curled into a bucket chair. I managed maybe ten minutes of actual sleep but gained enough rest to press on. In a race like this, even brief moments of stillness can be just as restorative as sleep.

Langdon Beck to Alston

Compared to day one, this leg was uneventful. The Cauldron Snout diversion was a tedious tarmac stretch but passed quickly. High Cup Nick offered its usual stunning view, followed by more boggy ground. Anticipating a swollen waterfall crossing, I climbed higher for an easier route. I should have taken photos, but keeping moving was the priority.

In Dufton, I met my friend Jim, who had come to support us, and was glad to see Stu Smith at the checkpoint. It was bittersweet, as friends Jim and Zoe had retired there, reminding me of my own withdrawal at this point last year. After a meal and shedding some layers, I set off toward Cross Fell under a sunny afternoon sky.

As night fell, I joined Yvonne and Kevin on the climb. A full moon over a cloud inversion at Great Dun Fell made for a breath-taking moment, and a stop at Cross Fell captured the shelter beautifully.

Alston Checkpoint

Gregg’s Hut was, as always, manned by my friend John Bamber, serving chili noodles and hot chocolate. I stuck to my routine, having another rat pack meal. Leaving with Jo, I struggled to keep up with her strong walking pace—my heavy pack and lack of training with it were taking their toll.

The final stretch to Alston checkpoint was a muddy, slippery track. Volunteers once again provided incredible support. Exhausted after just ten minutes of sleep the previous night, I waited over an hour for a bed. Though I had hoped for four hours, I managed about 90 minutes before waking at 4:30, feeling wobbly. A shower helped, followed by a much-needed feast. This was an emotional low point, but the kindness of the checkpoint staff kept me going. Quitting was never an option, but their patience and care gave me the strength to continue.

Alston to Bellingham: A Slow, Muddy Odyssey

Leaving Alston at daylight, I faced unfamiliar trails leading to Greenhead. While the weather was pleasant, the ground was a different story. The mud was relentless, with each step a battle against terrain that seemed determined to consume me. The ground wasn’t just slippery—it was alive, pulling at my shoes with every stride.

Progress felt like an act of sheer willpower. My feet sank into the muck, and some steps required real strength just to extract my shoes. I watched in awe as Nikki Arthur glided past, seemingly unaffected by the terrain. For me, it was a slow struggle, each step a careful negotiation with the ground beneath me. The mud came in many forms—sticky clay, thin watery sludge, and deep peat bogs that threatened to swallow me whole.

My knee rehabilitation, unexpectedly, became my saviour, helping me stay upright as I threaded a precarious path through the mud. Balance became an art, and every step was a calculated risk. At one point, I met a man assessing the Pennine Way with his two sprocker dogs. He shared insights into the rapid deterioration of peat bogs from freeze-thaw cycles and the damage caused by passing runners, which added a new layer to my understanding of the trail’s challenges.

This wasn’t just walking—it was a battle against the landscape, a slow, grinding struggle where every meter was a hard-won victory.

Greenhead: A Brief Sanctuary

The terrain seemed endless, and I broke up my ration pack into three sittings, finding brief respite on a wooden bridge and atop ladder stiles. When the A69 appeared on the horizon, it felt like a mirage—a glimmer of hope. I celebrated with a short jog, a tiny rebellion against the day’s struggle.

Greenhead arrived like an oasis. Drew, a familiar volunteer, had transformed the checkpoint into a haven with basic comforts: flushing toilets, running water, and a hot drink. The simple luxuries felt like profound relief. I replenished my supplies, readying myself for the next challenge—Hadrian’s Wall and the unknown stretch to Bellingham. The event continued to test my endurance, one challenge after another.

A Solitary Journey: Moonlight, Mud, and Moments of Reflection

The cold, windswept night was dominated by the challenging ground rather than the weather. As I climbed towards Hadrian’s Wall, a vibrant orange glow silhouetted the ancient stones, with the moon casting an ethereal light across the landscape. In that moment, I felt completely alone—no runners ahead or behind—just me and the vast, silent surroundings. It was a transcendent moment in an endurance event that had already spanned 13 years.

Brief encounters with fellow runners punctuated the solitude, including Kevin, an accomplished runner with an interesting backstory. We were later joined by Hem Rana, who seemed to glide effortlessly through the challenging terrain that had slowed us down.

Horneystead Farm provided a welcome respite, with vegetable soup and coffee offered by Helen, the owner. A 10-minute nap restored just enough energy to continue to Bellingham, where volunteer kindness awaited. Familiar faces like Mick Browne offered comfort as I replenished calories and snatched another 30 minutes of rest.

Leaving Bellingham in the cold afternoon, I felt surprisingly positive. The mud had been relentless, a true "Type 3 fun," but I was fueled by stubborn determination. My feet had stayed dry, and I found myself trotting occasionally, enjoying the companionship of my shadow. The forest track to Byrness threatened to lull me into sleep, so I called my daughter for distraction. At Byrness, I fueled up with mince, mash, and Swiss roll with custard, preparing for the final challenge—the Cheviots. This extraordinary journey was nearing its end.

The Cheviots: A Final Marathon of Endurance

The final 26 miles through the Cheviots tested my resilience. I started the race with no expectations, burdened by nearly four years away from long distances, illness, injury, and a temperamental knee. The accumulated fatigue from days of movement weighed heavily.

My knee, already compromised, worsened during a steep descent on Hadrian’s Wall. Each downhill became a careful negotiation, and a short scramble in the Cheviots required creative problem-solving. Fatigue, more than the cold wind, became my primary adversary. Progress slowed to a crawl, and at 3:39am, I texted Spine HQ, took a 7-minute sleep, and pushed on to Hut 1 for much-needed rest and care from the team. After an hour of sleep and some coffee, I was revived.

With Brian, another Spiner, I continued through the wild landscape. A surprise encounter with Paul from Rothbury brought joy, as he offered hot tea and ginger cake, giving me a burst of energy. At Hut 2, I reunited with my friend Antonio, and despite his own challenges, his positivity uplifted me. We climbed Schill together, and when my pole broke, he kindly offered me one of his.

The final miles mixed exhaustion with moments of beauty. Supporters cheered, and the Spine media team captured a rambling, sleep-deprived interview. Eventually, the finish at Kirk Yetholm appeared. I jogged through the arch, a defiant final gesture.

Reflecting on the race, I realize it’s never just about the miles or terrain. It’s a test of resilience, preparation, and the will to continue when everything urges you to stop. The challenges were a backdrop to personal discovery and growth, a metaphor for life. Each step, checkpoint, and connection was a part of a larger story of human endurance. As I finished, I wasn’t just a Spine finisher—I was a testament to the extraordinary strength within all of us when we embrace the unknown and keep moving forward.

Thank you

A huge thank you to the Spine Race team, checkpoint volunteers, and SST volunteers for your care and encouragement, especially at my lowest moments. Thanks to my fellow runners and the supporters cheering us on. Thanks also to James Thurlow and Open Tracking for ensuring competitor safety and keeping dot watchers captivated. And a special shoutout to Di Newton for providing social media updates throughout the event.

My deepest gratitude to my coach, Kim Collison, whose belief and guidance helped me overcome challenges and transform my mindset this year. To everyone who sent messages of support, thank you – your words meant the world. If my journey has inspired you, let it propel you toward your own goals. “You’re never too old to set a new goal or dream a new dream.”

Finally, I’ve been raising sponsorship for Headway South Cumbria, honouring the support they gave when my child suffered a head injury. Your donations not only kept me moving forward but will also help those navigating acquired brain injuries. Thank you for your generosity.